Scientists are developing custom weather forecasts for Nigeria’s agriculture sector, equipping farmers to feed the country’s growing population.

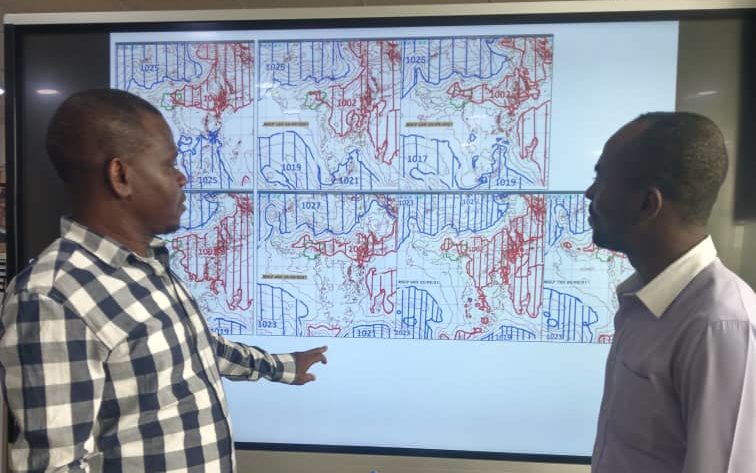

Meteorologists at the Nigerian Meteorological Agency (NiMet) are independently developing their own sub-seasonal forecast products for the first time through the GCRF-African SWIFT programme. The result is a critical step towards achieving food security and improving livelihoods across the country.

The custom forecast products are created using data supplied by the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts through the WMO Subseasonal to Seasonal Project Real-time Pilot Initiative.

The products are shared with end users to inform decision-making in economic sectors ranging from agriculture to insurance, healthcare, construction, water resources, natural disaster management and the general public, impacting millions of Nigerian people.

“The forecasts we are producing now wouldn’t be possible without GCRF-African SWIFT,” said Dr Kamoru Abiodun Lawal, General Manager of Numerical Weather Prediction at NiMet and Post-Doctoral Research Fellow for the African Climate and Development Initiative (ACDI) at the University of Cape Town.

“Instead of relying on ready-made products provided by a European organisation, through timely access to original data, we can generate more products than ever before and tailor them to each user’s unique needs. Our users appreciate the ability to be directly involved in developing custom climate information that supports decision-making. Because of this, there is more trust in forecast information.”

Weather forecasts key to climate resilience

According to Mr Richard Nzewku, Climate Change Specialist for the Nigerian government’s Climate Change Adaptation and Agribusiness Support Programme (CASP), tailored forecast information provided by NiMet has continuously improved decision-making for farmers, supporting national ambitions to achieve food security for Nigeria’s growing population.

“Before partnering with NiMet in 2017, farmers never really had organised climate information to support decisions. Instead, it was mostly guesswork based on observations of the environment,” he said.

For example, clouds forming could be interpreted as a sign of early rains, encouraging farmers to start land preparation. However, in the case of a false onset, crops may go weeks without necessary moisture, leading to devastating crop failures, Nzekwu explained.

Designed to provide climate information advisory services to the agriculture sector, the CASP programme works with NiMet to provide forecasts to 663 village areas and approximately 104 local governments across seven states, reaching an average of 56,000 farmers annually. Nzekwu adds that as more farmers understand climate change adaptation, the programme continues to expand.

“For the first time since 2017, every village in the CASP area got access to information about the onset date, dry spell periods, length of the growing season, volume of rain expected, and cessation date. Farmers were able to make informed decisions about what to plant and when, as well as what actions to take to ensure their crops didn’t fail,” said Nzekwu.

“We started seeing benefits in the very first year of working with NiMet. A farmer called to ask when the seasonal rainfall prediction would come. He had successfully used forecast information to prepare for irrigation during a dry spell in 2017 – this was major a breakthrough.”

Farmers depend on new climate information

In addition to increasing confidence in, and uptake of climate information, Nzekwu says the partnership between CASP and NiMet has also given farmers an opportunity to advocate for the development of new products.

“One year, a farmer in Kebbi State planted rice towards the end of the calendar year. The wind was very strong, and he had to continuously irrigate his farm to reduce stress. He used a lot of resources to irrigate one crop, so he didn’t see much benefit,” explained Nzekwu.

“Another farmer in Zamfara State planted trees at the boundary of his farm, close to the main road. When I asked why, he explained that there was too much wind coming from that direction, causing him to lose his crop. The message I received was that NiMet needs to inform farmers about wind direction and speed, not just rainfall. Through this type of feedback, we are able to shape the information that NiMet provides to better support farmers in achieving food security.”

While the CASP programme is set to end in 2020, Nzekwu and Lawal both say ensuring farmers continue receiving tailored forecast information is key to building climate resilience and supporting livelihoods.

“We have gained confidence in developing custom climate information and have built trust with our users. Ongoing and unhindered access to this data will allow us to continue providing forecast products that Nigeria’s economic sectors have grown reliant on,” said Lawal.

This work is part of African SWIFT Testbed 2, a two-year initiative to improve forecasts in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and neighbouring countries on sub-seasonal timescales – one to four weeks into the future.